The reliability and resilience of the United States electric grid is a paramount concern for state and federal policymakers and regulators. As extreme weather and physical and cyber-attacks on grid infrastructure have led to outages of increased duration, scale, and impact on power customers and communities, policy and regulatory attention has shifted toward innovative investments to improve grid resilience.

Numerous state and federal statutes and non-legislative state actions, such as governors' directives, have focused on the deployment of resilience investments, such as microgrids, as a tool to help mitigate the impacts of power outages, integrate more clean energy within the grid, support more localized control of electricity generation, and other goals. In particular, microgrids provide significant resilience benefits with their ability to island and maintain critical loads during outages. Many State Energy Offices and Public Utility Commissions (PUCs) have been tasked by their governors and legislatures with translating this interest into action by designing programs, policies, rules, and regulations for microgrids. As a result, the National Association of State Energy Officials (NASEO) and the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC) created this framework to serve as a resource and guidance for developing a state microgrid policy, program, or regulation.

This framework provides relevant background information for State Energy Offices and PUC consideration, regardless of their state's microgrid landscape, through examples from peers as states across the country have implemented varying strategies to enable microgrids. It is a reference for state officials to consult when faced with new statutory authority or a non-legislative impetus to revise existing or create new microgrid programs and / or regulations. In addition to state officials, this framework can be a valuable tool for federal, state, and local policymakers, investor and consumer-owned utilities, consumers, community groups, and other stakeholders seeking to understand the complex policy and regulatory environment of microgrids, the roles of State Energy Offices and PUCs in supporting microgrid development and deployment, and how to engage with policy, programmatic and regulatory initiatives.

Although State Energy Offices and PUCs have different electric distribution system roles, each is interested in ensuring the safe, reliable, affordable, and beneficial deployment of resilience projects, such as microgrids, to achieve their state's policy goals and requirements.

In exploring this framework, the authors also recommend that readers reference previous publications from NARUC and NASEO, including papers on valuing resilience, user objectives and design approaches, funding and financing options, and clean energy microgrids.

States are taking various steps to facilitate the deployment of microgrids that improve resilience and further the achievement of other policy goals, such as integrating clean energy, expanding access to electricity, reducing energy costs, and/or addressing the needs of underserved communities. The urgency by which states approach the development of microgrid programs, policies, and/or regulations are affected by numerous factors, including:

Typically, microgrid programs and regulations may originate within state legislation, which encourages or requires State Energy Offices and / or PUCs to initiate decision-making processes, to launch a microgrid grant program, or otherwise reduce barriers to microgrids. Statutes creating microgrid programs often include appropriations of taxpayer resources to support programs; those requiring regulatory action may not include specific public appropriations but may be funded by utility ratepayers and clarify the purpose the regulations should work towards. Statutes often include definitions of microgrids and other relevant terms. Additionally, a microgrid may not inherently consist of clean or renewable energy resources. Requirements regarding fuel source or emissions reduction will need to be legislated, negotiated, or established by regulatory rulemaking, if not already specified.

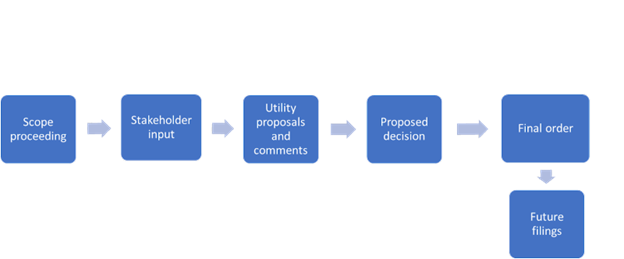

Translating a statute into regulatory and / or programmatic actions can take anywhere from one to five years, or even longer depending on the complexity of issues and number of stakeholders involved. Microgrid regulatory initiatives at the California and Hawaii commissions were initiated by statutes passed into law in 2018; both dockets remain open and active as commissioners, staff, and stakeholders move from simple or short-term actions to more complex, multi-stakeholder, and long-term questions. While stakeholders may push for speed, State Energy Offices and PUCs are faced with the responsibility of weighing public interest considerations, programmatic objectives, the scope of their statutory authority, and other factors before taking action. Stakeholder input is a critical component of any regulatory or programmatic effort, and State Energy Offices and PUCs may organize in-person and / or virtual workshops, technical working group meetings, written notices for public comment opportunities, and other chances for stakeholders to provide information and perspectives to regulators and program staff. Stakeholder input is further explored in sections below.

When considering the market for microgrids, a state's energy policies, regulatory structure, and utility market structure, as well as the utility's ability to own generation and/or storage resources connected to the distribution network, are important drivers of microgrid development and deployment. For investor-owned utilities, there is substantial diversity between states in vertically integrated markets versus for restructured electric utilities. In the former, utilities own and operate generation, transmission, and distribution assets. Vertically integrated utilities may own and operate microgrids in their service territory, with costs to be recovered from customers via rates. In the latter, utilities own and operate distribution (and in some cases, transmission) networks; however, generation is opened to independent power producers bidding into competitive power markets operated by an independent system operator (ISO) or regional transmission operator (RTO). The ownership and operation of microgrids is subject to competition, and electric distribution utilities in restructured environments may be formally prohibited from owning and / or operating parts or all of a microgrid. Still, regulated utilities own the distribution network in either scenario, and any microgrid distributing electricity from one customer to another, across a public right-of-way, requires the use of utility-owned, PUC-regulated distribution infrastructure and must coordinate with the distribution utility. This issue is commonly identified as a barrier to multi-customer microgrids; regulated utilities and PUCs are responsible for the safety of the distribution network and require some level of visibility and / or control over distribution-connected resources. Single-customer or campus microgrids can generally interconnect without use of utility infrastructure.

Consumer-owned utilities, such as municipal utilities or rural cooperatives, are generally not regulated by PUCs. This means they might have different challenges and opportunities associated with microgrids. For example, some rural cooperatives might have limitations on how much electricity they can self-generate through existing contracts with power producers. Others have a limited customer base which reduces the amount of financial costs they can absorb. In addition, they may need to educate their members on the benefits and costs associated with different types of microgrids (e.g., single-customer, campus, multi-customer). For those consumer-owned utilities serving rural areas, though, microgrids may provide greater benefits by defraying costs associated with transmission line upgrades or the installation of new lines. Rural areas that are served with an islandable community microgrid provide additional resilience benefits for areas that are at higher risk of outage in the absence of a microgrid. In many states, State Energy Offices have a close relationship with consumer-owned utilities and can support them in overcoming potential challenges to implementing microgrid programs (Farrell, 2019).

While State Energy Offices can provide policy and programmatic pathways and PUCs can provide regulatory pathways for microgrids, legislative activity often underpins these efforts through appropriations, requirements, or standards. Governors and legislatures often direct State Energy Offices to conduct studies or analyses to inform additional executive orders or legislative actions in support of microgrids. While these are not the only options to move microgrid policies and programs forward, it is an important area to consider given the prevalence of legislative interest. According to the National Council of State Legislatures (NCSL), there are 21 states and one territory (Puerto Rico) with substantive microgrid laws or laws that at least mention microgrids (Shea, 2022). NCSL's Microgrids: State Policies to Bolster Energy Resilience outlines specific legislative actions that can be taken to encourage development of microgrids, including:

Such legislative activity can play a critical role in shaping the work of State Energy Offices and PUCs as it may require the State Energy Office to set up a grant program or require the PUC to establish a microgrid tariff or undertake a proceeding to streamline or improve microgrid regulations. The state legislature, State Energy Office, and PUC can also work together through information sharing forums on the benefits of microgrids for different use cases and potential barriers to deployment. This can provide an understanding of what action is needed and how it can be addressed through policy or regulatory action, and whether and how legislation can support such actions. In addition, legislation can establish a state-specific microgrid definition, support methodologies to value the resilience benefits of microgrids, and codify the incorporation of equity considerations in state microgrid programs.

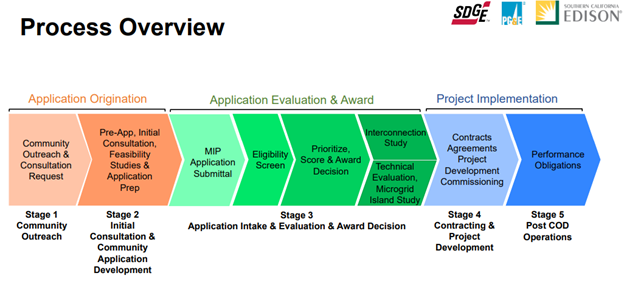

California Senate Bill (SB) 1339, enacted in 2018, is a representative example of how legislation can shape state activity regarding microgrids. SB 1339 directs the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to take action with consultation of the California Energy Commission (CEC) and California Independent System Operator (CAISO) and identifies key issues holding back microgrid commercialization in the state. Challenges include addressing how microgrids can play a role in implementing policy goals, how microgrids operate in the current California regulatory framework, and how microgrids support California's policies to integrate a high concentration of DERs on the grid (California Legislative Information, 2018). The legislation also defines what a microgrid is within the larger state energy system, which is helpful in designing programs and determining what kinds of projects would be impacted by the legislation. The CPUC, with the consultation of the CEC and the CAISO, were directed to take several actions through SB 1339, including developing microgrid service standards, reducing barriers to deployment, forming a working group, and creating a standard that helps to streamline the interconnection process.

Since the bill was signed into law, the CPUC has initiated new rulemaking to determine how to approach the responsibilities outlined in the law, explored further in Section V. The CPUC has also organized a resiliency and microgrids working group to look at issues such as standby charges, multi-property microgrid tariff, and the value of resiliency (CPUC, 2021). Most importantly, as a result of the legislation, California has established a microgrid tariff and a microgrid incentive program, discussed in more detail in Section V. In 2022, additional legislation was passed to support the CEC in funding microgrids across the state. The CEC Distributed Electricity Backup Assets Program is accepting applications for projects, including microgrids, that provide load reduction and back-up generation to support the electric grid during outages and other extreme events (CEC, n.d.). Additional CEC programs that provide significant opportunities for microgrid developers and provide resources that encourage utility customers and communities to invest in microgrids include the CEC Long Duration Energy Storage Program, Demand Side Grid Support Program, Clean Energy Reliability Investment Plan, Food Production Investment Program, and Industrial Decarbonization and Improvement of Grid Operations Program.

In addition to California, several other state microgrid programs and regulatory initiatives are in place. In June 2022, Colorado passed significant legislation that advances microgrid deployment in the state. HB 22-1249 requires the Colorado Energy Office, with support from the Colorado Department of Local Affairs and Colorado Resiliency Office, to develop an electric grid resilience and reliability roadmap. The roadmap must include information on potential legislative, administration, statutory, or rule changes regarding microgrids and outline key factors related to safety, development, maintenance, and deployment; metrics for evaluating cost and benefits; financial and technical support; and stakeholder outreach opportunities (Colorado General Assembly, 2022a). The roadmap will also need to examine the potential of microgrids for improving resilience and reliability and identify critical facilities where projects could be sited. The final roadmap will need to be shared with the Colorado Public Utilities Commission.

A second piece of legislation in Colorado, HB 22-1013 (the Microgrids for Community Resilience Grant Program), appropriates $3.5 million to the Colorado Department of Local Affairs and the Colorado Energy Office for rural electric cooperatives and municipal utilities to develop microgrids in areas at risk from natural disasters (Colorado General Assembly, 2022b).

In Oregon, the Oregon Community Renewable Energy Grant Program, which provides grants for planning and developing resilient clean energy projects, including microgrids, was developed as a result of Oregon HB 2021. The legislation appropriated $50 million in funding to the Oregon Department of Energy to establish the program. There is also legislation moving through the Oregon State Legislature, HB 3378, that would require the Oregon Department of Energy, with the PUC, to study and submit findings on the development and adoption of microgrid systems and use of microgrid systems for increasing electric grid and energy resilience (Oregon Legislative Assembly, 2023).

Legislative activity can put in place standards or appropriations that lead to significant investments in state microgrid projects. In 2021, the North Carolina State Legislature passed SB 509, which creates a revenue fund for the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality's (NC DEQ) State Energy Office to, among other initiatives, provide technical assistance to support communities in conducting a needs assessment of prospective clean energy microgrids to address resilience needs. The technical assistance will include support for designing the projects, addressing permitting and siting challenges, and understanding the potential financing options (North Carolina General Assembly, 2021).

State leadership may also establish a goal regarding how much electricity should come from renewable sources by a certain date and specify what percentage of that electricity should come from DERs such as microgrids. The Vermont Renewable Energy Standard was established through legislation and requires that the state obtain 10 percent of its energy from distributed generation by 2023 (NCSL, 2021). These decisions can have direct implications for the State Energy Office and PUC and can lead to programmatic, policy, or regulatory actions related to microgrids.

It is also important to consider the role State Energy Offices and Governors can play in influencing and moving legislation forward. Many State Energy Offices are responsible for advising the Governor on energy issues; and developing comprehensive state energy plans, energy security plans, and roadmaps to meet resilience and clean energy goals that can lead to legislative action. For example, in the Connecticut state energy plan, the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection specifically outlined their efforts to advocate for legislation that was supportive of community microgrids (Rickerson, 2022).

In Washington, when Governor Jay Inslee took office in 2013, he encouraged the state legislature to approve funds for a Clean Energy Fund with support from the Washington Department of Commerce. The Clean Energy Fund provided funds to grid modernization projects, including microgrids. The NASEO-NARUC Microgrid State Working Group also provides a platform for states to discuss potential policy recommendations to facilitate legislation.

Microgrid programs, policies, and regulation also may advance without legislative activity. Examples include the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin's Office of Energy Innovation's Critical Infrastructure Microgrid and Community Resilience Center Pilot Grant Program (CIMCRC) and the New Jersey Town Center Distributed Energy Resources (TCDER) Microgrid program. CIMCRC was funded through the U.S. State Energy Program administered by the U.S. Department of Energy and was developed through recommendations from Wisconsin State Energy Office staff regarding the importance of proactive resilience planning (Wisconsin PSC, 2021). The New Jersey Board of Public Utilities initiated the TCDER microgrid program after Superstorm Sandy wreaked havoc on the state's electricity grid, with funds coming from the New Jersey Clean Energy Program budget. Additional examples are explored throughout this framework. In 2022, the North Carolina DEQ embarked on a state-wide effort to engage stakeholders and collect data useful to identify potential sites for resilience projects that foster equitable decisions and improve underserved communities. Results from this project highlight the value of combining various datasets to gain greater insights into potential areas for resilience investments, like microgrids, to address these siting challenges and to better understand solutions. As part of the project, the Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA) developed a mapping tool to enable users to view all of the data layers used in analysis on the same map to gain a solid understanding of how data can be used to define resilience needs (Smart Electric Power Alliance and NC DEQ, 2022).

Legislative activities often lead to the appropriation of funds to State Energy Office-led microgrid grant or incentive programs or State Energy Office-led roadmaps, feasibility studies, or data collections on critical facilities and other relevant information. State Energy Offices frequently lead these statewide activities as they can convene stakeholders and analyze information from investor- and consumer-owned utilities, the private sector, local governments, and communities to determine beneficial investments for the state. Roadmaps, feasibility studies, and data collections may be conducted to determine ideal locations for siting microgrids in a state and to explore factors such as cost, energy source(s), inclusion of battery storage, and engineering design. They can also lay out challenges that may arise when deploying microgrids and outline the regulatory and policy structure that is in place, including potential cost considerations for the project and the viability of project completion. State Energy Offices may also look at potential community impacts or environmental justice / equity benefits, outline the state's priorities regarding microgrid development, such as supporting decarbonization goals or increasing resilience at critical facilities, and identify the key stakeholders who should be involved in and consulted throughout the process.

An example of a State Energy Office-led program is the Wisconsin Office of Energy Innovation's Critical Infrastructure Microgrids and Community Resilience Centers (CIMCRC) Pilot Grant program. This initiative awarded grants to 15 entities to conduct feasibility studies at critical locations across the state (Wisconsin PSC, n.d.). Recipients included tribal governments, utilities, the University of Wisconsin system, municipalities, and nonprofit groups (Wisconsin PSC, n.d.). Feasibility studies provide an opportunity to gather information prior to investing funds in the design and development of a project. Another example is the Kentucky "Regional Microgrids for Resilience" study conducted by SEPA and led by the Kentucky Office of Energy Policy. The study collected data on several key factors including population demographics, critical infrastructure facilities, natural hazards, and utility / electricity data such as power plants in the region, transmission lines, electric service areas, and reliability metrics (Smart Electric Power Alliance, 2021).

By defining a microgrid and its subcategories, PUCs can specify what conditions microgrid operators must meet and under what circumstances - if any - a microgrid meets the definition of a public utility subject to full rate regulation. In the District of Columbia (District), the D.C. Public Service Commission in Order No. 21172 issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking RM-48-2022-01 that establishes rules governing microgrids development in the District. The proposed rules provide microgrid development classifications, requirements, codes and standards. Under the proposed rules, multiple customer microgrids in the District are considered a public utility under District law and would be required to obtain a certificate of public convenience and be subject to the same cost-of-service rate regulation framework as an investor-owned utility.

Multiple PUCs have also advanced microgrid regulation through rate recovery for energy and services provided by microgrids. One goal of rate regulation is the avoidance of cost-shifting: when a customer is required to pay for a service they do not use or benefit from. Microgrids present challenges to the process by which PUCs typically set rates by bringing up questions about who benefits from microgrids during both blue sky days and energy emergencies, and thus who should pay for both fixed and variable costs of a microgrid. When a microgrid is in island mode during an outage or energy emergency and only provides service to the load within its footprint, the value of service that microgrid is providing is unavailable to ratepayers outside of that footprint. Therefore, ratepayer compensation for the microgrid's service can represent a form of cost-shifting because the energy it provides is only available to those loads within its footprint rather than the entire rate base. PUCs across the country have engaged in discussions and decisions about the proper cost allocation for microgrids, with many PUCs seeking further data to compare the costs and benefits of microgrids to other reliability and resilience investments such as additional generation, transmission, or distribution capacity or grid hardening practices.

State Energy Offices and PUCs generally share a need to seek stakeholder engagement and, in many cases, outside technical assistance as they undertake efforts related to microgrids. These tasks are undoubtedly familiar to state officials and are important factors in successful approaches to complex issues such as microgrid programs and regulations.

This section elaborates on these common needs, cites relevant state examples, and shares resources from NASEO, NARUC, the DOE, and National Laboratories that may assist State Energy Offices and PUCs. Further sections discuss the unique needs of each state entity.

A critical component of developing a state microgrid policy or program is stakeholder outreach and engagement. A state microgrid program or policy will impact multiple stakeholders, and it is important to get their feedback, hear concerns, and address challenges prior to the actual application process or implementation of a program. The actual steps that should be taken to develop a stakeholder engagement process will be outlined in further detail within the State Energy Office and PUC program development sections, but this section will provide some background on key considerations and strategies relevant to both State Energy Offices and PUCs. Project success can often hinge on whether enough stakeholder engagement was conducted.

Each State Energy Office and PUC will approach stakeholder outreach and engagement differently, depending on a variety of considerations including how they define disadvantaged communities, the location of critical facilities, their ultimate goal for the microgrid program, and their unique state circumstances and practices. To determine what the key considerations should be, some states have started by releasing a Request for Information (RFI). A public RFI would be an opportunity for not only developers, investor- and consumer-owned utilities, and engineers to provide feedback, but for the general public to share insights into what their concerns are or suggestions for how the program could be made more accessible. Input from customers and communities regarding uncertainties and objectives related to microgrids, as well as information on specific resilience needs, can assist the State Energy Office or PUC in structuring the program or regulatory initiative to address these needs.

The RFI should be widely publicized with information shared in both online forums and at in-person events. It can also lead to valuable feedback and information on how to develop definitions or specific terms early in the program's development. For example, in 2021, the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources released an RFI regarding the development of a municipal microgrid program. A particular emphasis was placed on receiving comments that define the public benefit of a microgrid, as required in the program design. The public benefit component was explained as the potential to provide back-up power to facilities supporting first responders or facilities that support food resources for the community, among other potential criteria (Rhode Island OER, 2021). Rhode Island is using feedback gathered from the RFI to modify and finalize their program structure and criteria.

States understand the importance of holding stakeholder events to gather information and hear concerns. Key stakeholders included in these forums may include community members, community-based organizations, consultants, local businesses, local government representatives, utilities, and other interested parties. State Energy Offices and PUCs hosting these events may wish to determine who the relevant stakeholders are in advance and target them to ensure a diversity of voices are in the room. States can reduce the risk of concerns being brought up post-program implementation by mapping out the stakeholders in advance and ensuring that all of the relevant stakeholders are present for the discussion. For additional resources, NASEO, NARUC, and the National Governors Association (NGA) have released several guides that can provide information to states on State Approaches to Equitable Distributed Energy Resource Deployment, Participation in Decision Making, Energy Justice Metrics, and Customer Affordability and Arrearages.

Public comment and stakeholder roundtable events should be held at different times throughout the day to provide the greatest number of opportunities for the relevant stakeholders to attend. If the State Energy Office or PUC is hosting the event, they should also coordinate with other state agencies who can provide support and relevant information. These joint events can also reduce the burden on communities by only requesting their attendance at one event. For example, the state economic development agency may provide information on workforce opportunities and job training that will accompany the microgrid program rollout. The state emergency management agency can provide information on how the microgrids funded through the program may support emergency response efforts during an energy emergency such as a blackout. Establishing these relationships with other state agencies can streamline the program development process and help determine whether any additional legislation, policy, or regulatory action is needed.

The West Virginia Office of Energy (WVOE) engaged SEPA to provide support in developing their "Regional Microgrids for Resilience" study. As part of the study, two stakeholder meetings were held with a goal of not only engaging key stakeholders and sharing information on the project, but also obtaining feedback on certain study components including site selection suitability criteria and additional data sources that could be explored (Smart Electric Power Alliance, 2022). Stakeholders that participated in these meetings included the Sierra Club West Virginia Chapter, the West Virginia Public Service Commission, and the West Virginia Emergency Management Agency. These meetings resulted in critical determinations that impacted the overall results of the study: hospitals and military installations were not included in the final study due to a consensus on prioritizing critical facilities without existing backup generation for siting microgrids (Smart Electric Power Alliance, 2022).

These stakeholder events can also be an opportunity to discuss potential public-private partnerships or other funding opportunities to boost the grants available from the state. There may also be interest in developing a project team who can meet more regularly throughout the development of the program and provide direct feedback and support. For example, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center released an RFI to identify interested parties who wanted to participate in or provide services to a microgrid team applying for a funding opportunity (MassCEC, 2022). Interested groups included energy companies, consultants, municipal organizations, power providers, and software designers. Including community representation on these teams is also critical to maintaining local buy-in and having a direct connection to hear and address community concerns as they arise.

While microgrid experts are important, actively engaging with the communities, including key energy and environmental justice organizations, is also a critical part of the process. This can be done in several targeted ways beyond just hosting public comment periods. For example, the Oregon Department of Energy established an Advisory Committee to support the development of their Community Renewable Energy Grant Program, which provides funds for projects including microgrids. The Advisory Committee has several responsibilities including establishing program equity metrics, adopting a methodology to identify qualifying communities, and supporting statewide community outreach efforts. The Committee includes utility representatives, a tribal emergency manager, county commissioners, engineers, energy justice organizations, emergency managers, a resilience officer, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) (Oregon DOE, n.d.).

Given the complexities of microgrid programs, policies, and regulation, State Energy Offices and PUCs may need outside technical assistance, given the relative newness of microgrid programs. Technical assistance opportunities may be available through grants from state and federal agencies or the private sector, including grants to bring on additional staff or to facilitate information sharing. Local utilities may also be available to provide technical support. For example, the Alaska Microgrid Group brings together experts from different electric cooperatives across the state to provide technical assistance related to energy resource assessments, microgrid system design, policy conceptualization and analysis, and project management services (Alaska, n.d.) For states with a green bank, such as Connecticut, there may be resources available for technical assistance provided through the bank or one of the bank's programs.

For certain projects, retaining an outside organization as a contractor, based on a thorough, competitive RFP process, may be a good option. This contractor can provide support in developing a roadmap for the state or in conducting feasibility studies to identify prime locations for potential microgrids. These outside organizations can also help the state catalog critical facilities that could benefit from a microgrid. Additionally, outside expertise can help determine the best technical approach for a critical facility microgrid and whether a single-site microgrid or cluster of critical facilities may be best suited for a front-of-meter microgrid. There are various methods of defining critical infrastructure, and states may not have the time, staff, or financial resources to conduct a statewide effort to identify and collect data on all potential locations.

States may also look to technical information being provided by the National Laboratories and U.S. Department of Energy. Across the country, National Laboratories are working to develop microgrid technologies to meet different needs and developing resources and tools to be used by states and developers. This can be particularly useful for topical areas that may be in the early stages of RD&D, such as the intersection of electric vehicles and microgrids. Idaho National Laboratory (INL) is working on fast-charging station microgrids to address some of the challenges associated with charging capacity. These microgrids will be made up of high-power electric vehicle chargers, local generation from solar photovoltaic systems, and battery storage (Palmer, 2021). As INL develops these projects, they can serve as a model for states looking to explore similar opportunities. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory's (NREL) REopt web tool is used to optimize the siting and operation of microgrids, and there is a public version of the tool available. At Sandia National Laboratory, the 2022 Microgrid Conceptual Design Guidebook can be used to look at site-specific vulnerabilities and design microgrids to meet energy resilience needs (Broderick, 2022). Sandia has also developed a tool called ReNCAT, which further optimizes microgrid siting by looking at equity considerations in the form of a social burden index (Wachtel 2022). Similarly, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory has developed a Distributed Energy Resources Customer Adoption Model (DER-CAM) microgrid feasibility and planning decision-support tool.

Once a program has been implemented or applications released, the State Energy Office may serve as the hub, offering technical assistance to potential applicants or support for conducting feasibility studies. The State Energy Office could host technical workshops, which can serve as educational opportunities for applicants and bring in key stakeholders who will need to be involved in the process, such as utility representatives who can address concerns including how the interconnection process will be facilitated. This technical assistance may be especially valuable to applicants from disadvantaged communities, community-based entrepreneurs, minority-owned businesses, rural or small communities, or early-stage companies.

Cybersecurity for microgrids is another potential topic for technical assistance. Along with extreme weather events and intentional physical attacks on grid infrastructure, cyberattacks may cause widespread, long-duration outages with devastating impacts. DERs, including DERs that are microgrids, are vulnerable to cyberattacks, particularly given that they rely on numerous Internet-connected components and may be owned, operated, or maintained by unregulated entities such as private customers. State Energy Offices and PUCs were early to recognize the importance of cybersecurity, but have faced challenges incorporating cybersecurity planning and preparedness into existing processes. Further, high demand from investor- and consumer-owned utilities, consulting firms, and other state and federal agencies for cybersecurity experts has made it difficult for State Energy Offices and PUCs to build a reliable pipeline of in-house cybersecurity expertise.

The National Laboratories, DOE, NASEO, and NARUC have developed resources to assist State Energy Offices and PUCs in improving the cybersecurity of critical infrastructure and the energy grid. NREL, for example, manages several initiatives to develop cybersecurity standards for DERs, including an effort with the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and Underwriters Laboratories, Inc. (UL) to revise existing standards for DERs and DER hardware to improve cybersecurity (NREL, 2022). NARUC hosts a suite of cybersecurity resources for PUCs on its website, funded by DOE's Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER). NARUC has developed a comprehensive set of resources, collectively called the "Cybersecurity Manual'', to help PUCs gather and evaluate information from utilities about their cybersecurity risk management practices. These resources include overarching guidance on developing a commission strategy to implement their own cybersecurity practices, as well as question and assessment tools for utilities to assess their own cybersecurity risk profile. These tools are applicable to investor-owned utilities, as well as smaller third-party energy suppliers, such as microgrid developers. NASEO and NARUC collectively lead the Cybersecurity Advisory Team for State Solar (CATSS) initiative to help mitigate cybersecurity risks associated with solar energy. The initiative brings together State Energy Offices, PUCS, and private sector representatives to share challenges and opportunities around solar cybersecurity and to develop tools that can serve as actionable resources for states as they engage in public-private partnerships and develop policies, programs, and regulations to support these efforts.

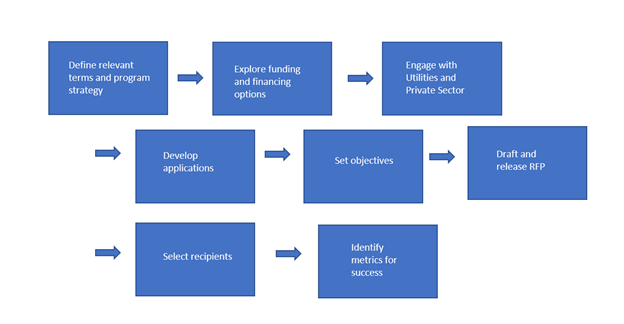

This section highlights some of the steps and key considerations State Energy Offices could follow to develop their own state microgrid policy or program, recognizing that these steps may not be applicable to all State Energy Offices and can be adjusted to fit the structure and goals of each state. Many of these steps are modeled after successful and established state microgrid programs, which can provide lessons learned and background on potential challenges that might arise in the development process.

The first step when developing a microgrid policy or program should be to define several key terms including microgrid, hybrid/multi-customer microgrid, and mobile microgrid. This can be done through legislation, regulation, a state roadmap, or in the initial program description. It is important that a definition is accepted state-wide; coordination between the State Energy Offices and other relevant state agencies such as PUCs and State Emergency Management Agencies might be needed to come to a consensus. Many State Energy Offices utilize the DOE definition of "[A microgrid is] a group of interconnected loads and distributed energy resources within clearly defined electrical boundaries that acts as a single controllable entity with respect to the grid. A microgrid can connect and disconnect from the grid to enable it to operate in both grid-connected or island-mode" (Ton & Smith, 2012). For those State Energy Offices who are looking for a more specific definition or one that more closely aligns with their program goals, they can adjust the DOE definition or develop a new one. There may be instances where a State Energy Office is only looking to fund fully-islanded projects or microgrids at critical facilities. All of this can be clarified and expanded upon in a state-wide definition. Two examples of how states have defined microgrids themselves are outlined below in Table 1.

Table 1: Example Definitions

| California | A microgrid means an interconnected system of loads and energy resources, including, but not limited to, distributed energy resources, energy storage, demand response tools, or other management, forecasting, and analytical tools, appropriately sized to meet customer needs, within a clearly-defined electrical boundary that can act as a single, controllable entity, and can connect to, disconnect from, or run in parallel with, larger portions of the electrical grid, or can be managed and isolated to withstand larger disturbances and maintain electrical supply to connected critical infrastructure (California Legislative Information, 2018). |

| New Jersey | A Town Center Distributed Energy Resources (TCDER) Microgrid…is a cluster of critical facilities within a municipal boundary that may also operate as shelter for the public during and after an emergency event or provide services that are essential to function during and after an emergency situation. The critical facilities are to be connected to a single or a series of DER technologies that can operate while isolated and islanded from the main grid due to a power outage (NJBPU, n.d.) |

Hybrid or multi-customer microgrids are currently rare and lack the capabilities for wide-spread commercial deployment. According to a Boston University study, these microgrids can be defined as "microgrids that provide multiple energy consumers the ability to self-supply electricity during grid outages while continuing to leverage the existing power grid during the majority of the time…" (Boston, 2018). Mobile microgrids are portable and often feature the "plug-and-play" model that allows them to be installed quickly (Siemens, n.d.). The Iowa Economic Development Authority provided funding to a mobile microgrid initiated by the Iowa National Guard made up of solar panels and lithium-ion batteries on a large shipping container. The microgrid is designed to be shipped on truck, train, or ship and can be up and running in only a couple of hours (Maloney, 2020).

Once State Energy Offices have determined the focus and definition for their microgrid program, they can look at the program structure and strategy. Legislative action may dictate the scope, structure and goals of the program. Some goals could include expanded access to microgrids in underserved communities, enhanced resilience for critical facilities, reduced energy costs, reduced grid congestion, expanded renewable energy, or exploration of innovative workforce and /educational opportunities.

The following excerpts of program descriptions for the Resilient Maryland Program, led by the Maryland Energy Administration (MEA), and for the Town Center Microgrid Program, led by the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU), which also serves as the State Energy Office, provide different examples of how to characterize a description. For MEA, the program's purpose was kept general to incorporate projects beyond microgrids, while New Jersey BPU focused on the impetus for the program. Both provide concise information to potential applicants on program goals.

Program Purpose: "Resilient Maryland is provided to help organizations identify potential ways to incorporate DERs into organizational energy management plans that improve resilience and sustainability, reduce energy burden, and safeguard essential infrastructure, services, and businesses from prolonged power outages. In its FY22 year, the program is seeking projects that pursue creative solutions, incorporate innovation, explore potentially replicable and scalable project models, and enhance energy equity to Maryland communities experiencing vulnerabilities and challenges" (Maryland Energy Administration, n.d.).

Program Description: "The New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (NJBPU) initiated the TCDER Microgrid program as a result of Superstorm Sandy. Our State learned that further measures are needed to help New Jersey become more resilient, particularly with respect to critical facilities" (NJBPU, n.d.)

State Energy Offices should then consider their approach to the actual program development by asking questions such as: How much specific technical information will the applications need to provide? Will technical assistance be provided by the state to applicants? Will the program fund feasibility studies or actual project deployment or both? What are the funding and financing options for the program? Who will have authority for the program within the office? These questions will be explored in more detail below.

According to a 2018 NREL study, the average cost for a campus or institutional microgrid is $3 million, for a commercial or industrial microgrid $4 million, and for a community-owned microgrid $2 million (Giraldez, Flores-Espino, MacAlpine, and Asmus, 2018). Costs can be impacted by the type of generation being used to power the microgrid, the use case for the microgrid, the location of the microgrid, and the design process. As a result, State Energy Offices, PUCs, and project developers will be looking for different financial mechanisms to support the development and deployment of these projects, as well as the ability to draw lessons out of funded projects to facilitate the implementation of similar projects in the future to provide increased benefits at lower costs to ratepayers and/or taxpayers. In California, for example, the CEC has provided ratepayer funding to support the development of 65 microgrids statewide in the past decade through its research programs. Through these projects, the CEC has advanced the science of microgrids and worked to address market barriers to deployment that will benefit electricity ratepayers.

The financial mechanisms available to customers procuring microgrids are varied. They can include private, state, and federal funding and financing tools to facilitate all or part of the project RD&D costs. Costs to consider include conducting a feasibility study, engineering and design needs, and construction, operation, and long-term maintenance of the microgrid. State Energy Office-facilitated grant programs may provide full support for project completion or focus on just one of these mechanisms. Since certain funding may only be applicable to one part of a project, it is crucial for microgrid customers (e.g., municipalities, commercial and industrial customers, critical facilities, and others) to be aware of the full portfolio of options.

Funding a State Microgrid Program

In addition to the funding opportunities outlined above, State Energy Offices setting up a State Microgrid Grant Program will also need to consider how this program can be funded. While it is important for State Energy Offices to understand the potential opportunities available for funding microgrid project RD&D, there are also funding streams available to fund the development of a microgrid program. As discussed earlier, funds can be appropriated to the State Energy Office through the State Legislature for setting up a program. Funds appropriated to the State Energy Office through the legislature will usually provide specific information on the goals of the program, how much funding is available over a certain period of time, and other criteria that may be required such as developing a state resilience roadmap to coincide with program development.

The U.S. State Energy Program (SEP), administered by the U.S. Department of Energy, can be utilized to support microgrid programs and policy efforts.

Additional federal funding opportunities include BRIC, HMGP, and CDBG for disaster relief (explored in more detail below). States can utilize the funds from these programs to fund project buildout and scoping. These programs emphasize the resilience benefits of microgrids and are available for states to apply for.

Potential Funding Sources for a Microgrid Project

In addition to the described State Microgrid Grant program, additional options exist to support the financing of specific microgrid projects. These options are explored in depth in the NASEO-NARUC paper Private, State, and Federal Funding and Financing Options to Enable Resilient, Affordable, and Clean Microgrids but a brief overview is included below to provide some context to this framework.

Public-Private Partnerships

Public-private partnerships such as energy-as-a-service, energy savings performance contracts, and Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) loans are one financing model available for microgrids. These are opportunities to form a joint investment between public sector and private sector partners to boost the amount of capital available for a certain project. In October 2022, the Brookville Smart Energy Depot opened in Silver Spring, Maryland. The project utilizes a 6.5-megawatt solar powered microgrid to charge up 70 buses and was developed through a public-private partnership between the Montgomery County Department of General Services (DGS) and AlphaStruxure. MEA also provided a $300,000 grant from its Public Facility Solar Grant Program to support the project (MEA, 2021). AlphaStruxture provides energy-as-a-service, which means they design, finance, construct, own, and operate the microgrid and receive revenue generated from the microgrid as compensation (Cramer, 2021). According to MEA, this model will reduce risk to the county through avoidance of certain budget impacts and upfront costs (MEA, 2021).

Federal Funding

Federal funding opportunities include the Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA) Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program, FEMA's Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD) Community Development Block Grants for disaster relief (CDBG-DR). These funding sources might be augmented by state funding sources. The NY Prize Microgrid program run by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) and the Governor's Office of Storm Recovery (GOSR), for example, provided funds to local communities, businesses, and utilities to design and develop microgrids across the state. When identifying potential awardees, NYSERDA and GOSR looked at which projects were also eligible for CDBG-DR funds. For those projects that are eligible due to work with private utilities, location, natural disaster impacts (and other criteria), GOSR and NYSERDA worked to provide funding, including up to $20 million of CDBG-DR funds for construction.

The BRIC program awards grants to state governments, Tribes, and local governments to support projects that improve resilience capabilities and reduce the risk of disaster damage. In Fiscal Year 2021, 788 sub-applications were submitted across every state and territory, with 53 projects from 19 states selected for further review (FEMA, 2022). One of these projects, from the state of New Jersey, will turn a community center into a resilience hub. The center will be equipped with a solar array and microgrid for power resilience among other measures to better protect the community from flooding damage and other repercussions (FEMA, 2022). More information on the BRIC program and other federal funding can be found in the NASEO-NARUC Private, State, and Federal Funding and Financing Options to Enable Resilient, Affordable, and Clean Microgrids report, and NASEO's State Action Guide for Energy Resilience Projects Technical Guide and Quick Guide

In November 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA, also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) was signed into law and several of the resulting programs provide funding opportunities to support the development of microgrids. While many of the programs are still being set up and are time-limited, State Energy Offices should be aware of opportunities to apply for relevant programs and how the implementation process will work. They may also need to be prepared to coordinate with other state agencies, local governments, and investor-and consumer-owned utilities on implementing the funding. Some examples of relevant programs within IIJA include some opportunities under the Grid Resilience and Innovative Partnerships (GRIP) program, the Energy Improvements in Rural or Remote Areas (ERA) program, and the Clean Energy Demonstration Program on Current and Former Mine Land (CEML). The GRIP program can support microgrid deployment for enhancing adaptive system capacity during disruptive events from electric grid operators, electricity storage operators, electricity generators, transmission owner or operators, distribution providers, and fuel suppliers (U.S. DOE, 2022). The ERA program has released an RFI on the program which has a goal of supporting innovative energy projects in rural or remote areas including developing microgrids. IIJA also includes section 40101(d) which outlines potential resilience investments eligible through a state, tribal, or territorial formula grant program, including the use or construction of DERs, such as microgrids to enhance system adaptive capacity during disruptive events. Importantly, no new electricity generation qualifies under 40101(d) but all other components of a microgrid are eligible for funding. CEML is looking to fund microgrids sited on mining sites.

In addition, in August 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was signed into law, which provides credits and incentives to support microgrid deployment. These include the Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit, Production Tax Credit, and Investment Tax Credit (ITC). Under the ITC, an additional bonus credit for microgrids located on Indigenous land or in areas serving low-income communities is available (Cooper, 2022). The Greenhouse Gas Reduction fund, led by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), may also potentially be utilized for microgrid projects. The EPA has released a Request for Information (RFI) on the program, but initial information suggests that clean energy microgrids (not supported by any kind of greenhouse gas emitting back-up) may be eligible for some of the funds. $27 billion will be provided by the EPA to provide grants for projects, such as funding distributed technologies in low-income and disadvantaged communities and other projects that help to reduce or avoid greenhouse gas emissions (U.S. EPA, 2022).

State Financing Programs

State funding and financing programs include revolving loan funds, grant and incentive programs, state-supported green banks, green bonds, competitive grants, and utility rate recovery. These are outlined in more detail in Table 2 below. State grant programs may also require the applicant to provide a certain amount of cost-share or matching funds, especially if a project is estimated to go over a certain price. Cost matching is also usually required to cover a certain percentage of a project's cost that will not be covered by federal funds.

Table 2: State Funding and Financing Programs (Cramer, 2021)

| Funding / Financing Model | Advantages | Challenge | Applicable Phase | Existing Model in Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

State Energy Revolving Loan Funds |

|

|

|

Washington Clean Energy Fund Microgrid |

|

Grant and Incentive Programs |

|

|

|

New Jersey Town Center Microgrids |

|

State-Supported Green Banks |

|

|

|

Connecticut Green Bank Microgrid Financing Program |

|

Green Bonds |

|

|

|

Camden County, New Jersey Microgrid |

|

Competitive Grants |

|

|

|

NY Prize Microgrid Competition |

|

Utility Rate Recovery |

|

|

|

Commonwealth Edison Bronzeville Microgrid and Duke Energy Hot Springs Microgrid |

When developing a state microgrid program, State Energy Offices can utilize their relationships with local governments, investor- and consumer-owned utilities, and the private sector. These key stakeholders can provide insights into their needs and challenges associated with microgrid development and help make program applications stronger and more accessible. State Energy Offices are uniquely positioned to maintain these relationships and develop programs with their support. Consumer-owned utilities (such as municipal utilities and rural electric cooperatives) often do not have the same resources as larger, investor-owned utilities and might experience unique challenges related to adding additional renewable generation, resiliency, cost, transmission build-out, and financial and staff capacity constraints. Often, the customer base for these utilities is spread out over remote or rural areas. Municipalities are also often dealing with resiliency issues at critical facilities and could benefit from state funding to reinforce these locations. Several existing state programs, specifically target municipalities and consumer-owned utilities, and can serve as models for other states. The Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources developed a report, Resilient Microgrids for Rhode Island Critical Services, that specifically looks at how microgrids can support municipalities. In addition, the Colorado Microgrids for Community Resilience Program, targeting municipal-owned utilities and rural electric cooperatives, also utilizes a state developed Climate and Social Vulnerabilities Mapping Tool (guidance can be found here) for municipal-owned utilities and cooperatives so they can better understand their vulnerabilities and opportunities for microgrids that address, among other items, climate and environmental justice concerns.

Regarding the private sector, State Energy Offices should reach out to DER providers, engineers, developers, and other relevant players to determine what technologies they are able to provide and what the potential costs and benefits would be for a project. This can also be an opportunity to explore potential public-private partnership models (see Section B for more information). The private sector can also provide insights into the current market and how future projects will be impacted by market changes. Innovative companies may also be interested in engaging with State Energy Offices developing programs that will incentivize private sector investment in microgrid research, development, deployment, and commercialization (NASEO, n.d.).

Programs will usually involve a competitive application process to determine who will receive funds, for how much, and for what kinds of projects. Sample applications will be included in the annex for reference, but some key items to keep in mind will be explored here. The State Energy Office staff responsible for developing the application should first consider putting out a Request for Information (RFI). This will be an opportunity for key stakeholders to provide input into the program structure and application process. This is especially important for ensuring that the program application process is fair and accessible to all, as community groups or other interested parties can express concerns about cost match or application timelines that can be addressed before the final Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) or Request for Proposals (RFP) is released. The Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources released an RFI prior to program development to get input on criteria for applicants and other relevant information (see Section III.A above for more details). This reduces the potential for a top-down approach with little to no stakeholder engagement. A deadline should be set for how long the comment period will be open and a public webinar can also be held to provide clarity on the RFI and share potential questions the state would like to see addressed in stakeholder responses. Rhode Island hosted a webinar that walked through the RFI and provided an opportunity for potentially interested applicants to ask questions (Rhode Island OER, 2021).

With most states looking to incorporate equity into their broader office and program structure this will also need to trickle down to the application process for grant programs such as a microgrid program. For example, the Oregon Department of Energy's Community Renewable Energy Grant Program made clear that priority would be given to applicants from communities of color, low-income communities, Tribes, rural areas, and other underserved groups. Applications should be accessible to Tribes, low-to-moderate income communities, non-English speakers, and other vulnerable groups. States can utilize their own tools and data to define disadvantaged communities and ensure the proper outreach and resources are available to these communities. Resources can include application assistance forums with translators and other support and a clearly laid out instruction guide. The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection included comprehensive instructions for applicants to read to ensure that no incomplete applications were submitted by mistake or due to lack of experience applying for state funding.

The goals for the program should be clear in the application so that potential applicants can best cater their projects to the program purpose and needs of the state. For example, potential goals can include enhanced resilience, electric grid services (i.e., preventing energy loss and load management), supporting critical infrastructure, integrating DERs, supporting municipalities needs, and/or decreasing greenhouse gas and particulate matter emissions. State Energy Offices can determine which of these criteria are the most important and require potential projects to address one or more of them. There also may be a targeted audience for applications, which should be clearly articulated on the program website and all accompanying materials. The Colorado Energy Office and Department of Local Affairs have released application guidance on their microgrid program. These materials not only emphasize that eligible applicants are limited to cooperative electric associations and municipally-owned utilities, but clarify that "proposed microgrid project(s)/plans must serve one or more eligible rural communities located within the applicant's service territory" and that the communities must be dealing with risk from extreme weather/climate, infrastructure, or socio-economic or environmental justice concerns (Colorado Department of Local Affairs, 2022). Potential projects also need to improve the resilience of a "community anchor institution," such as a school or hospital, and projects with less of a reliance on fossil fuel-based generation will be prioritized. The application provides a clear definition of what constitutes a rural community and "community anchor institution".

State Energy Offices are also encouraged to develop a supplemental application instruction guide and Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) document. These will serve as important resources for potential applicants as they navigate the application process. It will also provide insights to underrepresented groups interested in applying who might not have experience in applying for a state grant. In the FAQ, potential questions include whether cost matches are required, what partnerships are allowed, and whether certain projects would qualify based on the program description. The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection updated the FAQ documents on their website several times when their Microgrid Grant Program was open for applications. An example can be found here which demonstrates the large volume and variety of questions that a State Energy Office may expect to receive. As Connecticut did, these FAQ pages should be shared on the program website and be updated frequently. In addition to these resources, State Energy Offices could also consider developing a fillable template for applicants to enter data on their proposed project and determine if it aligns with the goals. These templates can also serve to help applicants determine potential financing avenues and see how bringing in cash or in-kind match would improve or expand the project's viability.

Microgrid projects cover a wide range of applications and locations in the state and should support site-specific and state-wide goals. These projects can be an opportunity to test innovative microgrid configurations or DER portfolios, such as co-locating electric vehicle chargers and microgrids. Certain programs will only fund feasibility studies, while others will finance the entire process. Potential project locations for feasibility studies and final projects include military installations, hospitals, water/wastewater facilities, communications infrastructure, schools, transportation facilities, emergency centers, and local government buildings. There can also be considerations made for awarding a diversity of projects that will provide backup support to different communities and locations. Awards may also be given for full project construction or for feasibility studies.

When states are deciding whether to focus a program on only feasibility studies or full project development, there are a few items to consider. Funding feasibility studies may minimize the risk of project failure or incompletion down the road. Some of the items applicants could be expected to study and collect data on include energy use/cost, hazard vulnerabilities, projected benefits of the microgrid, stakeholder engagement, identification of critical facilities, load profiles, energy burden, sizing, duration, fuel supply, and potential deployment and location sites. Grantees may not have had the resources to collect this information without the funding from the state, so it sets them up for better success when actual development and deployment commences. States may also review the outcomes of the feasibility studies to determine whether to fund full development of a project or not. This can be made clear in the upfront feasibility study application, or it can be made clear that the funds are for feasibility studies only and that construction costs will not ever be available. This makes grantees aware that they should be exploring other funding options. In addition, a program may be set up to award two different grants over a staggered timeline. For example, the Colorado Microgrids for Community Resilience Grant Program opened grants for planning in February 2023 and grants for implementation and construction will open in Spring 2023. Technical assistance will be provided for both options. Some example activities eligible under the planning/feasibility studies include developing an action plan and roadmap, evaluating existing infrastructure vulnerability, engaging with communities to identify their needs, and establishing a community's potential based on scale, size, and cost. For the implementation and construction grants, new microgrid facilities will be funded, and specific eligible elements include energy storage, microgrid controller, and vehicle-to-grid projects (Colorado Department of Local Affairs, 2022). These are draft guidelines, but provide examples other states could replicate. When not funding feasibility studies, states may require more technical information in the upfront application to support the actual feasibility of a project to ensure it is shovel ready.

After an application has been finalized and a program is ready to launch, State Energy Offices will need to draft and release a Request for Proposals (RFP) or Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA). Some examples will be linked in Appendix A: Further Reading. These RFPs and FOAs cover a wide range of necessary and detailed information including eligibility requirements, program parameters, selection criteria, deadlines, required forms and materials, and other relevant details. Information that may be covered in the RFP or FOA would also include key definitions, projects that will be considered, the review process, submission instructions, and how much funding will be available. The Resilient Maryland program run by the Maryland Energy Administration contains an overview of all the information needed to be included in a project proposal within their FOA, such as a description of each part of the microgrid project development and how it will be funded and a detailed budget for what the applicant is looking to be reimbursed for. States may also require letters of support to be submitted with the application, as the Wisconsin Office of Energy Innovation did (Wisconsin PSC, 2021). Applicants were required to submit letters of support for a feasibility study of a potential microgrid in the state from the local distribution utility and participating facilities (Wisconsin PSC, n.d.).

These RFPs and FOAs should be announced on social media and shared on the State Energy Office's website. The State Energy Office should also have a running database of relevant contacts to share RFPs and FOAs with ranging from private sector stakeholders to community-based organizations, depending on the eligible applicants. There can also be efforts made to ensure Tribes, disadvantaged communities, consumer-owned utilities, and local governments have the necessary materials and resources to complete the application. For example, allowing it to be submitted in paper form or translating the application instructions into other languages can make it more accessible. The application should have a fillable template for applicants with clear instructions to eliminate confusion. States should also determine how much technical information they will want included in the application. For example, the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) required applicants to submit information such as details on the microgrid controller and load management plan and data on how the microgrid will withstand extreme weather events. The technical data required can differ depending on the goals of the program or how much information the state would like to have on hand before selecting recipients of the funds. In round one of their solicitation, the only round that required project feasibility assessments, Connecticut DEEP also limited applications to their program to those who had already submitted a project feasibility application and been given the green light to move ahead. They also provided feedback to those municipalities who were not given the go ahead on what would make a stronger proposal in the future. Staggering applications and requiring a shorter feasibility application or concept paper first can reduce some of the burden on communities and local governments by not requiring them to fill out a full application that has no chance of receiving full support. In addition, local governments may need longer timelines for application development and feasibility studies. The Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources outlined some of the reasons, which include prolonged processes for decision making, procurement, and energy/facility capital improvement project development, and longer administration processes (Celtic Energy, n.d.).

When selecting recipients after the FOA or RFP has been released, there are a variety of different strategies to consider. These State Energy Office grant programs are usually competitive programs with applicants selected based on their application and how it aligns with the considerations of the review committee and necessary criteria. A review committee should be set up to provide support during program development and implementation and be given clear responsibilities, such as establishing program metrics, determining the program purpose and qualifying projects, and helping to engage potential applicants across the state. The State Energy Office could reach out to potential committee members directly or put out a request for interested parties. The ultimate goal is to have a committee that will bring different perspectives to the application review process and provide insights that the State Energy Office might not have. Potential committee members can include representatives from Tribes, investor- and consumer-owned utilities, local governments, emergency managers, developers, community members, and more.

A ranking scale can be used to rate proposals based on how they align with the program goals and numbers awarded by each member of the review committee. Potential considerations can include equity metrics, which include the number of communities that will be served by the microgrid, jobs created, the resilience benefits of the project, and how much stakeholder engagement and partnerships were facilitated with local communities. Other potential metrics include resilience benefits, such as hours of service provided during a power outage. States can develop an evaluation form that highlights the criteria being reviewed, how a certain score can be achieved, and the final score. For example, an application review committee may look at what the resilience potential of a project is and rank it from 1-5. In December 2022, the Oregon Department of Energy released the funding opportunity announcements (FOA) for round two of their Community Renewable Energy Grant Program. Oregon included a competitive review criteria chart in the FOA which looked at items such as strength of the planning project team, location of the project within a community, use of an equity framework to guide development, prior investments in energy efficiency at the project location, and more. Each item was given a numerical score, and applicants would be ranked on the competitive review scores and recommendations from the review committee.

Applicants should be made aware of a timeline for application announcements and be given an approximate deadline for when award notifications will be shared. When announcing the recipients of the Community Renewable Energy Grant Program, the Oregon Department of Energy shared that 68 applications had been received and 21 projects were selected. The review committee looked at project feasibility and strength, equity considerations, cost savings, economic development, and other criteria in the process. They also shared a timeline on their website with details on when announcements would be made (Oregon Department of Energy, 2022).

State Energy Offices should be prepared to provide continued support and engagement with their awardees. The Oregon Department of Energy, after announcing program awardees, outlined their next steps which included finalizing performance agreements and releasing an initial batch of funds (Oregon Department of Energy, 2022). The process for awarding grants may differ from state to state, but announcements should be made publicly and, if possible, efforts should be made to notify applicants who were not selected in advance. State Energy Offices can also provide feedback on these applications and encourage applicants to apply for future rounds of funding. State Energy Offices may also wish to explore cybersecurity concerns with the awardees and provide resources to mitigate potential threats (explored in more detail in the technical assistance section above).

Metrics for success of a project are varied, but a state should be aware of their goals and timeline for the project. This will help mitigate delays or funding concerns in advance. For example, DOE's program goals include "...developing commercial-scale microgrid systems (capacity of less than 10 MW) capable of reducing outage time of required loads by more than 98% at a cost comparable to non-integrated baseline solutions while reducing emissions by more than 20% and improving system energy efficiencies by more than 20% by 2020," (U.S. DOE, n.d.). This goal provided DOE with actionable metrics to track program success. The Maryland Energy Administration requests that grant recipients submit monthly progress reports that include a milestone completion checklist, description of progress on the project, hours worked, and schedule progress (MEA, n.d.) By collecting these reports monthly, it allows MEA to see what potential challenges have arisen and the plan to address them before the project has gotten too far along. Feedback collected from grantees also allows MEA to see what changes should be made for future iterations of the program.

A comprehensive example of a State Energy Office microgrid program is included below to illustrate the different steps involved throughout the entire process from the enabling legislation to awarding grants.

Table 3: Connecticut Microgrid Grant and Loan Program

Connecticut: Microgrid Grant and Loan Program - Pilot Program

Enabling Legislation: Substitute Senate Bill No. 23 Public Act No. 12-148

In 2012, the state of Connecticut passed An Act Enhancing Emergency Preparedness and Response which, in part, directed the Connecticut State Energy Office and the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) to establish a microgrid grant and loan pilot program.

Primary Objectives:

DEEP was responsible for establishing a microgrid grant and loan pilot program to support local distributed energy generation for critical facilities. The loans and grants were to be used for supporting the cost of design, engineering services, and interconnection infrastructure for the microgrid. Critical facilities were defined as hospitals, police stations, fire stations, water treatment plants, sewage treatment plants, public shelters or correctional facilities, any commercial area of a municipality, a municipal center, as identified by the chief elected official of any municipality, or any other facility or area identified by DEEP. According to DEEP:

"The purpose of the Program is to solicit proposals to build microgrids in order to support critical facilities during times of electricity grid outages. The Program was developed in response to the Governor's Two Storm Panel's recommendation regarding the use of microgrids as a method for minimizing the impacts to critical infrastructure associated with emergencies, natural disasters, and other events, which cause the larger electricity grid to lose power (CT DEEP, 2013).

This chart will walk through steps that were taken in the pilot round of the program. Not all of these steps were replicated in future rounds, as DEEP incorporated lessons learned to improve the process.

State Energy Office Key Actions Timeline:

August 2012: CT DEEP issued a Request for Information (RFI) regarding the program requirements and selection criteria. The RFI outlined specific questions DEEP wanted feedback on and included information on the proposed program criteria. Some of the questions included in the RFI: